CC: CP - the Don’t miss Diagnoses

These are the immediate life-threatening diagnoses that you simply cannot miss. Thankfully, many times these are not subtle presentations, often recognized by nurses and paramedics prior to your evaluation.

According to UpToDate here are the acute Life-threatening conditions you should consider on EVERY CP patient.

Acute coronary syndrome

Acute aortic dissection

Pulmonary embolism

Mediastinitis

Tension pneumothorax

Pericardial tamponade

Let’s address each of these, with a slight change to the last 2 diagnoses on the list. While a small pneumothorax or pericardial effusion is not an immediate life-threatening condition, these are not diagnoses that you want to miss, due to the fact that these can worsen and result in mechanical compression of the heart.

Thus, our list of don’t-miss-diagnoses will include the following:

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

Acute aortic dissection

Pulmonary embolism (PE)

Mediastinitis

Pneumothorax

Pericardial effusion

Let’s start with the easiest diagnosis to rule out early —> PNEUMOTHORAX

Don’t wait to get a CXR on a patient with a tension pneumothorax!

Pneumothorax

A tension pneumothorax is most often the result of thoracic trauma or aggressive positive pressure ventilation and usually doesn’t present insidiously with a chief complaint of "chest pain." Rather these are acutely SOB, hypotensive patients and dying in front of you. A patient with a tension pneumothorax will be in extremis, hypotensive, tachypneic, and possibly cyanotic with exam findings such as a trachea pushing away from the side of increased pressure and absent breath sounds on the side of the pneumothorax.

Treatment for a tension pneumothorax is immediate decompression. Typically, the fastest way to do this is a needle decompression, which is beyond the scope and purpose of these posts but can be reviewed in many places and viewed in this video.

Spontaneous pneumothorax, on the other hand, can present with minimal signs and symptoms. Although these don’t often convert to tension physiology, that doesn’t mean it is not dangerous to be discharged home undiagnosed. I strongly suggest considering pneumothorax in every CP patient who presents AND thankfully, this can be ruled out at the bedside with bedside ultrasound!!!

“Lung sonography has rapidly emerged as a reliable technique in the evaluation of various thoracic diseases. One important, well-established application is the diagnosis of a pneumothorax. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of a pneumothorax in the management of a critical patient can prevent the progression into a life-threatening situation. ”

More on this later in our discussion on how to incorporate point-of-care-ultrasound (POCUS) into your physical exam, but in short look for lung sliding at the pleural line and evidence of lung below the pleural line such as A-lines or B-lines. Learn more at https://rebelem.com/ultrasound-detection-pneumothorax/ and https://www.pocus.org/pneumothorax-can-pocus-lung-help/.

Bottom line: You can easily diagnose pneumothorax on bedside ultrasound.

On to —> The THORACIC AORTIC DISSECTION

A thoracic aortic dissection (TAD) might be a bit trickier than a pneumothorax. Though rare, it has high mortality. Classically, patients are supposed to have pain radiating to the back with a tearing or ripping sensation. Hopefully, there is a pulse or BP deficit from one arm to the other that can clinch the diagnosis of ripping off an innominate vessel, but this is dependent on where the dissection goes and is not always present. Other vessels branching off of the aorta that are sheared off by the dissection such as the carotids can cause stroke-like symptoms.

Thus, you must always remember —> CP + neurologic symptoms can = very bad diagnoses such as aortic dissection. Don’t forget to consider this in those patients, but as stated previously, a dissection may not shear off carotid or upper extremity vessels.

It is also essential to consider this in every ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patient. A proximal TAD can shear off one or more of the coronary arteries that originate from the base of the arch. A non-perfusing coronary will, of course, cause a STEMI, but not the kind of STEMI we usually think of when a plaque ruptures and clot forms. Imagine if you could pick this up before a patient goes for coronary reperfusion when they really need aortic surgery.

Key takeaways:

Aortic dissections are rare but extremely dangerous.

CP + neuro deficit or radial pulse deficit = dissection until proven otherwise.

Lack of “classic” symptoms does NOT rule out a dissection.

Not every TAD has a widened mediastinum on chest x-ray (CXR)…

..wait, what??? I thought that’s why we got CXR?

CXR

-

Can't r/o dissection

CXR - Can't r/o dissection

More review at http://circ.ahajournals.org/

As you may have learned, thoracic dissections come in 2 flavors, which are useful in determining treatment, but not in making the diagnosis. The purpose of this discussion is to ensure that we never miss this diagnosis in patients presenting with CP. You simply must include thoracic aortic dissection in your differential diagnosis.

Like pneumothorax, the diagnosis may be very obvious from the clues discussed above; however, not every patient with this rare diagnosis has these findings. Thus, we must remember ALL the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of the disease.

High-risk symptoms of thoracic aortic dissection include...

Abrupt onset

Severe pain

Ripping or tearing sensation

High-risk patients are those with...

Connective tissue disease such as Marfan syndrome

Family history of aortic disease

Known aortic valve disease

Recent aorta surgery

Known aortic aneurysm

Finally, high-risk clues are..

Perfusion deficit - pulse difference, systolic BP differential in extremities, focal neurological deficit

Murmur of aortic insufficiency (yeah I would have to look that up too), but remember there can be a wide pulse pressure with aortic insufficiency as well (look up pulse pressure if you need to)

Hypotension/shock

With all these risk factors, is there at least a good clinical decision tool? Um, sort of. The Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS) is externally validated but not routinely used, in my experience. Not that I don’t find it helpful, as it does a great job of reminding me of all those high-risk features above.

The ADD-RS + D-dimer (the ADvISED study algorithm) attempted to combine the ADD-RS score with a d-dimer to rule out aortic dissection, but unfortunately has not been externally validated. This article from the Annals of Emergency Medicine 2015 also tried to use a D-dimer of >500 ng/mL as a cut-off to rule out TAD, and although it was very sensitive (98%), this was just not high enough for such a dangerous disease.

“Level C recommendation - In adult patients with suspected nontraumatic thoracic aortic dissection, do not rely on D-dimer alone to exclude the diagnosis of aortic dissection.”

I suppose if the patient had no major risk factors or features (see lists above) AND had a normal CXR and bilateral blood pressures AND you had a low suspicion (i.e. low pre-test probability), you could THINK about buffing your chart by getting a D-dimer <500. The problem with this approach is, are you prepared to CT aortogram all the patients with a high D-dimer???

Bottom line: You can't treat what you don't diagnose. Using the Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS) is a good start. It can remind you of important risk factors and disease features.

On to —> PULMONARY EMBOLISM

For obvious reasons, pulmonary emboli (PE) are included on the “don’t miss” list, and similar to aortic dissection, they can present along a spectrum from obvious to obscure. A massive PE will likely cause the patient to be hypoxic, tachycardic, and hypotensive (see official criteria in this article in Circulation). Severe right heart strain will lead to jugular venous distention (JVD) and the lungs will be mysteriously clear (unlike left heart failure). A massive PE is an immediate life threat, and you need to make the diagnosis early, just like a tension pneumothorax and aortic dissection.

Again, you could do a bedside echocardiogram early to look for right heart strain (more on this later). An unstable, hypotensive patient may not be stable enough to go for a CT to confirm the diagnosis. Learning to recognize right heart strain on bedside echo is not easy, but you don’t have to rely on just the images. Looking at the whole clinical picture, risk factors, symptoms, JVD without pulmonary edema, and other clues can lead you to the diagnosis even without exceptional echo skills, but when you combine your clinical suspicion AND rule out other causes that could lead to this patient being unstable - tension pneumothorax (discussed above) and pericardial effusion with tamponade (discussed below) - you can be much more confident in the diagnosis even without recognizing right heart strain.

An excellent discussion of right heart strain on echo can be found here - https://coreultrasound.com/5msblog-rhs-1/

More valuable teaching on identifying RV strain at the bedside can be found here - https://rebelem.com/diagnosis-right-ventricular-strain-transthoracic-echocardiography/

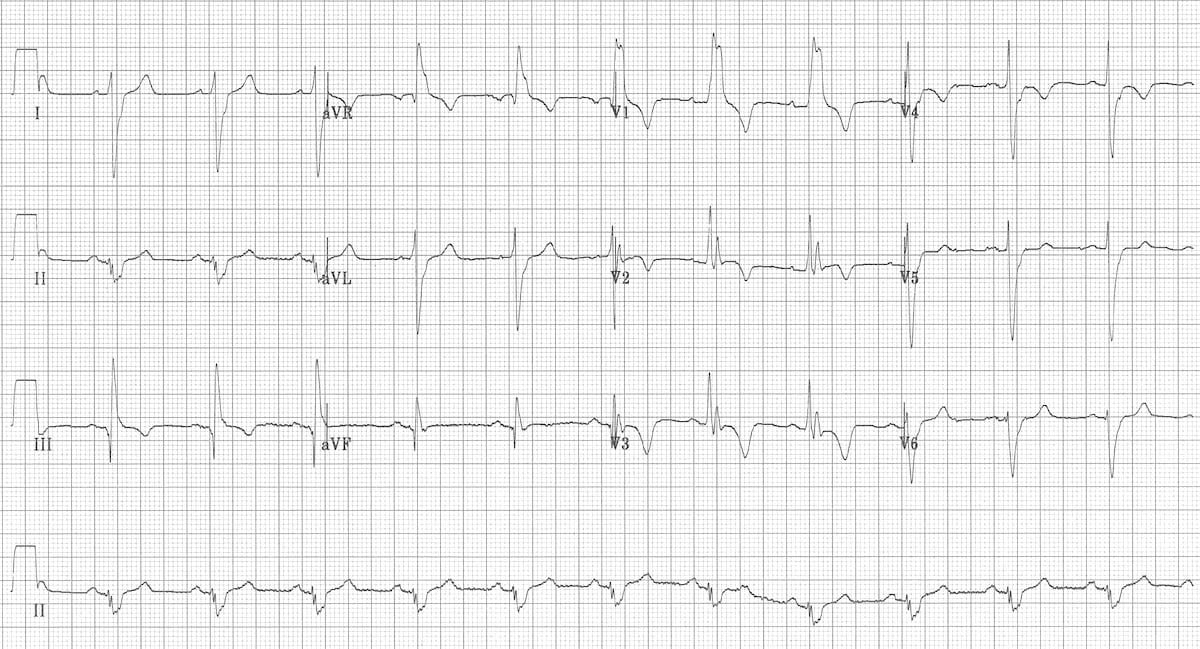

Speaking of right heart strain, an EKG is a quick and easy test that can also help your differential diagnosis. The most common EKG finding in PE is tachycardia, which is not all that helpful, but you also may have learned the “classic” SI QIII TIII pattern – deep S wave in lead I, Q wave in III, inverted T wave in III . Unfortunately, this “classic” pattern is only found in 20% of patients and isn’t sensitive or specific enough to be all that useful. Right ventricular strain and right axis deviation are also good to look for but don’t confirm the diagnosis completely (click here for more ECG findings from LITLF).

This EKG shows: RBBB, Extreme right axis deviation (+180 degrees), S1 Q3 T3, T-wave inversions in V1-4 and lead III, and Clockwise rotation with persistent S wave in V6 according to the smart authors at https://litfl.com/ecg-changes-in-pulmonary-embolism/.

Acute right ventricular dilatation due to massive PE - https://litfl.com/right-ventricular-strain-ecg-library/

Hopefully, this review helps clue you into all the signs and symptoms of a massive PE that you can assess right from the bedside, even before confirming with a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA), if the patient is stable enough to get one. Many of these may also be present on submassive PEs, and you should have a low threshold to get a CTPA on these more stable patients.

The difficulty in diagnosing PE lies in the patients who are not critically ill or only a few risk factors or signs that point toward PE as the #1 most likely diagnosis. These are usually patients who have smaller, sub-segmental PEs that we still cannot miss, due to the danger that they propagate and kill the patient. Therefore, we must be careful not to miss any PEs, no matter the size or presenting symptoms.

Thankfully, unlike aortic dissection, there are externally validated, well-known, and broadly accepted risk stratification tools that we can use in any patient with any chance of having a PE - which in terms of the undiagnosed CP patient, is every one of them without a confirmed diagnosis. Of course, we don’t have to use these tools in patients with a high risk of PE, but then again, who are those patients?

My advice is to apply the following pathway to every patient with symptoms that could be caused by a PE, unless you already have a confirmed cause of those symptoms (and even then, unfortunately, patients can have pneumonia and a PE).

What is your gestalt? After obtaining a history and performing a physical exam (that can include bedside echo), is PE the most likely diagnosis? If so, go straight to CTPA.

If you are unsure, or inexperienced, apply the Well’s Criteria for PE. Click the link or see the image below.

Any moderate or high-risk patients should get a CTPA.

If low risk, move on to step 3.

If low risk by Well’s Criteria for PE, apply the PERC score.

If any criteria are met on the PERC score, the patient needs further work-up; go to step 4.

If the PERC score is zero (and your pre-test probability of PE was < 15%, see image below), the chance of PE is < 2%, and no further work-up is needed.*

Obtain and interpret a D-dimer.

Your lab will likely have a pre-set cut-off for a “positive” result, usually 500 ng/mL. Below this is considered negative, and no further work-up for PE is needed.**

If the D-dimer is >500, then you can consider applying the Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs.

If above cutoff, proceed to CT PA.

If below the age-adjusted cutoff (10 x patient’s age), then the previously low-risk patient by Well’s Criteria, is almost zero risk for PE, and further work-up not necessary.

*In most cases, this effectively rules out PE or is not high enough to outweigh the potential risks of a CT scan (radiation exposure), but I suggest that you consider documenting this < 2% risk and even talk to your patient in a shared decision-making manner to discuss obtaining a CT.

**I also suggest discussing this with your patients, especially when the result is close to 500. I have seen D-dimer tests at 490 and 505 on separate occasions. I have told these patients that there is good evidence to support 500 as a cut-off, but this is not a magical number, and I have used shared decision-making in these cases.

For more information go to MDcalc.com and Well’s Criteria for PE.

For more information go to MDcalc.com and PERC score.

My pathway using Well’s criteria, PERC, and age-adjusted D-dimer is a bit wordy, but it is worth the read so that you can apply this to your medical decision-making (MDM).

Final Caveat - This pathway does not include pregnant patients who cannot be classified as low risk. The YEARS Algorithm can be helpful in these situations.

Bottom line: CT every patient at moderate or high risk for PE, and document your medical decision-making on every patient at low risk for PE with no alternative explanation of their symptoms. Feel free to use my pathway above as a template for your own MDM.

This is, in my opinion, the easiest bedside echo to interpret with huge ramifications if found. In fact, I'm so keen to find this diagnosis early, that I see value in teaching paramedics to pick it up in the field. See my review article, The Future of Ultrasound in Prehospital Resuscitation.

Finally —> Pericardial Effusion with Tamponade

The last of the immediate life threats to consider is cardiac tamponade, although, chest pain is not likely going to be the only presenting complaint. A patient with a pericardial effusion large enough to significantly disrupt LV function is going to be hypotensive. By definition, cardiac tamponade occurs when the amount of fluid in the pericardial sac compresses the ventricles and leads to a significant decrease in cardiac output and shock.

There are several causes of pericardial fluid accumulation, including blood from blunt or penetrating trauma which occurs with trauma. Cancer can also cause a pericardial effusion which usually slowly accumulates. These patients are more likely to present with signs and symptoms of hypotension, rather than just chest pain.

In terms of patients presenting with chest pain, pericarditis is the diagnosis that is important to catch. While this is a rare cause of pericardial tamponade, it is an important diagnosis to include in your differential.

Thankfully, a large pericardial effusion is the easiest diagnosis to make on bedside ultrasound! Just place the probe on the chest, and if you can get a view of the heart, you can see the black effusion surrounding it. Additionally, the lack of large effusion on bedside echo can rule tamponade out. Either way, bedside echo is your friend.

Bedside Ultrasound - for EVERY CP patient

As you can see from multiple images above, early ultrasound can help identify these life-threatening conditions. Early imaging by performing a bedside echocardiogram upon initial evaluation can rule-in or rule-out some of these life threats with fairly high accuracy. In fact, there are several protocols for pre-hospital point of care ultrasound (POCUS) that have varying success rates reviewed in this paper:

The Evolving Role of Ultrasound in Prehospital and Emergency Medicine - ClinicalKey

The absolute best way to improve your sonographic skills is to practice, practice, practice every time you see a patient with chest pain, even when you have a very low suspicion of finding anything on your exam. At best you will pick up surprising findings, at worst you will see many, many normal hearts while honing your technique.

What to document:

Dangerous causes of CP were considered with no evidence of pneumothorax on bedside exam and CXR.

The patient has *** risk factors for aortic dissection and symptoms were *** consistent with dissection. The Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS) was reviewed; *** further work-up was pursued.

The patient *** is hemodynamically stable with *** exam findings to suggest profound right heart failure (hypotension, clear lungs, JVD) that could suggest massive PE or pericardial tamponade. A bedside echo revealed *** pericardial effusion.

Sub-massive PE was also considered. The patient was *** risk by Well’s Criteria for PE. If low-risk, the PERC score was ***. Further evaluation with D-dimer is *** warranted. If the D-dimer is >500, then considered applying the Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs. The YEARS Algorithm was used in pregnant patients.

I’ll admit, that documentation above was a bit wordy, which is why I’m open to any of your suggestions. Thanks!

You did it!!! You considered life-threatening causes of CP.