Capacity vs Competency

Often, the terms capacity and competency are thrown around the ER and perhaps in a patient’s chart. You should be very careful in using these terms in your documentation with my advice being only use capacity as competency is a legal term.

What is Capacity?

On any given shift, you will encounter patients who are brought to the ER against their will and/or otherwise, do NOT want to be there. It is important for you, the clinician, to understand who is “allowed” to leave (legally) and who you, and the ER staff, can mandate to stay for treatment (legally).

The simplest example would be a child who has a broken arm and is demanding to go home. Of course, the parents and the staff are going to keep the child in the ED until the arm is splinted and the proper medical care is completed. The child is not able to definitively refuse care because they don't have the legal right or CAPACITY to understand what is in their best interest. They are just trying to avoid short-term pain without understanding the long-term consequences.

In the above instance, the parent or legal guardian has the capacity to decide for the child who is not legally competent, yet. Most adults (without cognitive impairment such as dementia), usually have the capacity to refuse treatment and leave the ED. The confusion lies in the patients who may be temporarily unable to make medical decisions for themselves. This might be a drunk patient or a schizophrenic who is suffering from psychosis and not perceiving reality. In these situations, patients may demand to leave the ER, but we (can legally) deem them unable to make an informed decision, and therefore, take away that right to refuse care. This means, the clinician decides that the patient does not have the capacity to decide, and thus, must stay for treatment.

Thankfully, most of these types of situations are black and white. Picture a very intoxicated college student who wants to leave but can't walk on his own and keeps falling asleep. It is not very hard for staff to keep him until he sobers up. Or think of a family that brings in a grandmother with dementia who is hallucinating. A caring family will often sit with Grandma, and calm her down, as well as consent for treatment on her behalf. No problem. These are not moral dilemmas, and everyone knows the patient cannot make a coherent decision on their own. Most times parents or family members want the patient to get treatment, even if it is against the patient's will.

Patients who are incoherent, intoxicated, obtunded, and/or clearly psychotic showing that they are not in touch with reality (interacting with things or persons who are not there = hallucinating or have beliefs or motivations that are bizarre = delusional) do NOT have the capacity to make an informed decision. This is typically self-evident to all involved.

One challenging situation that is unfortunately all too common in the ER is a sober patient, of the age of consent, and not showing signs of dementia or psychosis who made a suicidal statement, was brought to the ED, and wants to go home. Here most states have laws that allow or mandate medical professionals to hold patients against their will until seen by a psychiatrist. Instead of thinking of this as a separate category, I consider this a type of “temporary insanity” or not being in touch with reality, despite the fact a patients mental faculties may be otherwise unimpaired. I explain it to patients like this,

"I know you don't want to be here right now, but myself and the staff are concerned about your health and safety. I understand that you have had some suicidal thoughts and made some statements that have people concerned. Studies have shown that feeling suicidal is a temporary condition with many people recovering with the right treatment. Therefore, under the law, I am allowed to keep you in the ER and perhaps even in a hospital until you get better."

In these cases, a patient is deemed incapable of making their own decisions because they have made statements or gestures that they want to harm or kill themselves or others. For their safety, they can be held in the ED against their will. Unfortunately, this might sometimes require physical and chemical restraints, but it is usually clear legally and to staff that it is, in fact, our duty to keep these patients until they are admitted psychiatrically.

If you have worked in emergency medicine for any period of time, I am sure that you have encountered situations such as this, and I offer the above advice. I have had several arguments with patients about their rights, and it is important that we understand the components of capacity and the extension of the law to suicidal patients.

There are, however, some gray areas, and it is doubly important to state and document CAPACITY in your chart. You may encounter a lucid, un-intoxicated, normal-intelligence adult who is not suicidal and refusing care, wanting to leave the ED. Many times these are patients with mental health issues who are not overtly suicidal but sent to the ED to get help. Other times, a patient may recover from an accidental overdose and wake up demanding to leave. Finally, a walking and talking but clearly intoxicated person might make a bolt for the door. What do we do in these situations???

What we need to do is quickly establish if the patient has capacity to make medical decisions for themselves.

If you have ever been in this situation, this is the article you need to know...

Assessment of Patients' Competence to Consent to Treatment

Competency is a legal term handed out by a judge that says whether a person has the mental ability or soundness of mind to make decisions for themselves on their own. It is a long-standing judgment about a person’s mental ability. Capacity, on the other hand, is a term we medical people use to say whether a patient can make their own medical decisions at a specific point in time. To put it simply, competency is permanent (bestowed only by the court), and capacity is minute-to-minute.

It is imperative that you, a clinician, do not document the competency of the patient to make decisions unless you have been told or read that the patient was deemed no longer competent (by a court or other authority) and all medical decision-making henceforth must be done by a proxy. Instead, your role is to determine the capacity of a patient to make a sound decision, such as refusing care.

Thankfully, the law usually sides with medical providers erring on the side of caution, and there have not been successful lawsuits (to my knowledge) where a PA was found guilty of holding a patient against their will, so long as there was reasonable doubt about the patient’s capacity.

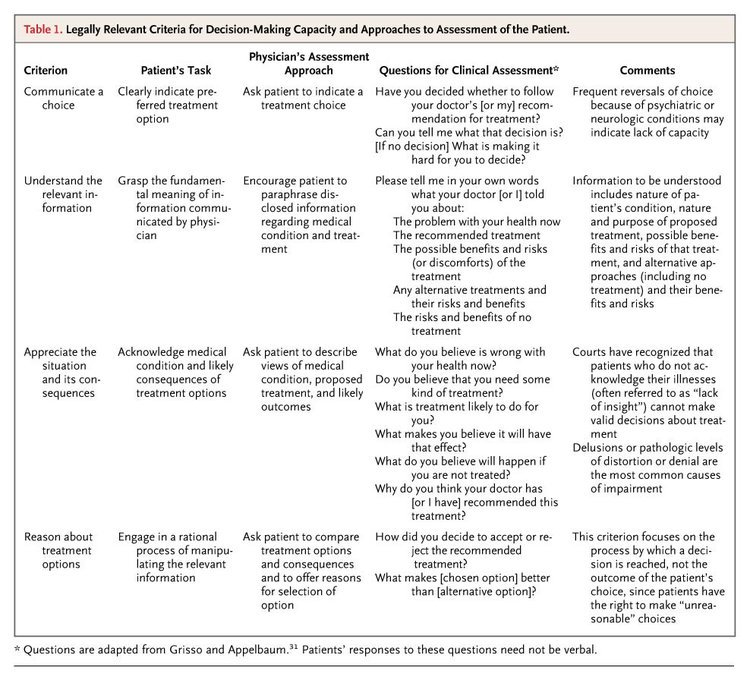

That being said, it is of utmost importance that you know the criterion to document well both when you are forcing a patient to stay or receive treatment against their will. The article above is free, and I will refer back to this chart often. The table below lists specific criteria that must be met for a patient to show that they have the capacity (outside of the above examples of suicidality and status as a minor). Most of these are common sense and do not need to be documented on every patient, but I recommend documenting at least one of the criteria below when making the judgment call that someone does NOT have capacity to make their own decision.

In summary, from the article above, a patient must "clearly communicate [his or} her decisions, understand the information about their condition, appreciate the consequences of their choices (especially the likelihood of death or permanent disability), and weigh the relative risks and benefits of the options, should they be considered competent to make a treatment decision."

Personally, I recommend documenting all above aspects on any patient who is refusing the treatment the you recommend, including staying in the ED for more tests. This could be a patient who signs out against medical advice or who is refusing a life-saving treatment due to religious reasons. In both instances, you should document why you think the patient does (or does not) have the capacity to make such a decision.

My template for this is…

The patient shows a capacity to make an informed decision by clearly communicating to me ***. The patient was told and able to repeat back to me the potential consequences of their choice including but not limited to death, disability, pain, suffering, loss of income, and ***. The patient chose *** as a reasonable alternative. Although I did not agree with this choice the patient appears alert, coherent, and able to make logical choices.

more on competency vs capacity

"Common law dictates that individuals possess autonomy and self-determination, which encompass the right to accept or refuse medical treatment. Management of medical treatment can be complicated in situations when the ability of the patient to make reasonable decisions is called into question. Our legal system endorses the principle that all persons are competent to make reasoned decisions unless demonstrated to be otherwise. This review will discuss the standards upon which capacity and competency assessments are made."

This quote is from the article: Competency and the Capacity to Make Treatment Decisions: A Primer for Primary Care Physicians which can be found here and is another valuable resource to review as is the quick hitting Capacity and Competence article on Life in the Fast Lane which summaries it as follows:

"Capacity is a functional term that refers to the mental or cognitive ability to understand the nature and effects of one’s acts

Competence is a legal term that can be defined as being “duly qualified: having sufficient, capacity, ability or authority” — in practice it requires health professionals to perform a functional test of competence to examine the ability of the particular patient to consent to the specific treatment being offered

Capacity and competence are often used interchangeably."

Other articles that are sited in the above references include:

Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, Fox E, Derse AR. Ten myths about decisionmaking capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(4):263-267.

Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

Again, I cannot stress enough how important it is to have these criteria memorized or able to quickly access (like bookmark this website!). A quick template I might make for a patient with questionable capacity might include...

The patient is able to clear state that he/she refuses *** treatment and is able to state my treatment plan back to me. Patient has shown insight into recognizing *** condition, and I have told them of the potential consequences of refusal of care which include, but are not limited to death, disability, pain, suffering, ***. The patient is able to articulate back to me these potential consequences and this was witnessed by ***. The patient has stated his/her reason for refusing care as *** and has stated *** alternative care plan.

Please let me know if you have a better, perhaps more concise or just more thorough, template that you use as clinician or as a group by emailing me at broughton.pa@gmail.com.